You know this blog is about the relationships, experiences and practices God uses to form us, right? Well, today I’m putting up a guest post from our daughter, Maggie. Most of you remember she worked in Northern Uganda this summer, doing an internship for her Masters in Public Health. Her experiences with the poor, and particularly with women, have formed in her, a heart for justice – the justice I believe is in God’s heart too. I’m sharing this as a little background before I post an update on the ways you have made a difference, joining in her work there.

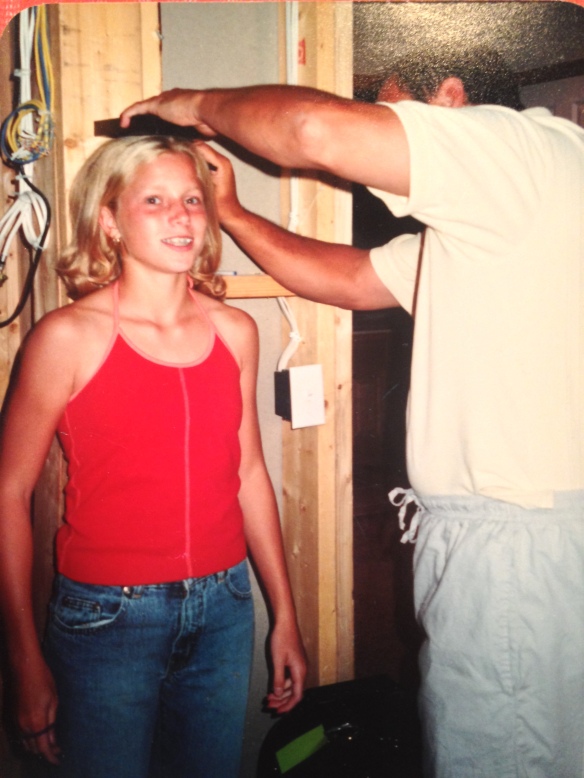

When I was 13 years old and growing up in Eden Prairie Minnesota, my most pressing concerns included: getting the braces off my teeth as soon as humanly possible, convincing my mother to allow me to wear a two-piece bathing suit (or get my cartilage pierced – I varied my advocacy agenda to better my odds), and counting down the days until I would finally get my first period. I was in a big hurry to grow up and these experiences seemed like pivotal pieces of my maturation strategy.

As each of these events came to pass, I felt more like a young woman (with the exception of the cartilage piercing incident, which resulted in massive infection and a disappointing trip back to Claire’s to have the earring removed by a “professional”). I vividly remember grinning ear to ear on the day I first got my period – I felt I had arrived. The smile quickly faded as I realized that I was home alone that day. Without the first idea of how to use a tampon applicator I was forced to spend those glorious first few hours of womanhood wearing a maxi pad that felt like the size of a diaper.

That feeling of helplessness was rare for me; I had plenty of adults in my life offering loving guidance throughout my formative years. Like many American teenagers, as the years passed, I learned how to drive, got an after-school job at Caribou Coffee, opened my first checking account and applied for college.

Most of my life has been typically American and very privileged. I was continuously encouraged with the Disney-esque message that I could be whatever I wanted to be and achieve whatever I set my mind to. Fortunately for me, my family and community had the resources that made those messages true. I traveled internationally on my own, learned to change my own flat tires and graduated from a 4-year university. At 22, I had a diploma, a passport full of stamps and limitless ambitions.

My sense of independence has led me to a few atypical opportunities that have reformed my worldview. Currently, I am writing these reflections as I sit in Northern Uganda. Here I work with a school of girls, many of whom are “child mothers,” girls who became pregnant at a very young age for various reasons. Their experiences differ vastly from my own adolescence. At 13, they are not thinking about ear piercings or bikinis. They certainly never looked forward to their first period. They likely dreaded it.

My students live in a region that is trying to heal after a 25-year civil war that was characterized by widespread rebel activity, the use of child soldiers and the abduction of young girls to be used as sex slaves. The geographic landscape is verdant but the outlook for Ugandan girls is bleak. They don’t look forward to their first period because they cannot afford underwear. Or soap, or pads, or school fees.

Nobody is telling these young women that they can be whatever they want to be.

Their vulnerabilities are palpable, and often preyed upon. Parents marry their daughters off at a young age to shed their financial responsibility. Men offer school fees, or soap, or towels, to young girls with the expectation that they will receive sex in return. Independence is a foreign concept to many of my students – the world they have grown up in does not provide them with choices.

Poverty happens to them. Marriage happens to them. Sex happens to them.

These ladies are survivors of unimaginable circumstances. They study for high school exams with babies swaddled on their backs. They are incredibly strong. I am not here to do anything for these girls, but rather to facilitate their learning and growth. I want to see them strategize and hack their own solutions to the daily health, hygiene and education challenges they face in their communities.

Not everyone is handed a Disney dream, but we are all born with the inherent power and potential to reform the circumstances we face. I dream of the day when these ladies will go out into the world, like I did, armed with a diploma, a passport full of stamps and limitless ambitions.